In 2024, Berkeley published a first of its kind study quantifying heavy metals in tampons. Researchers at Fort Lewis College quickly took action.

“I was actually just scrolling and it came up on my news – this article that Berkeley had looked for the first time to see what metal contaminants there were in tampons,” said Dr. Callie Cole of the FLC Chemistry Department. “I was kind of taken aback by how much they quantified in the tampons.”

Over in Chemistry Hall, a small team led by Cole focuses on studying the presence of lead, arsenic and cadmium in tampons. The researchers have analytically quantified these elements in tampons and gained preliminary results as to whether or not they leach out of tampons during use.

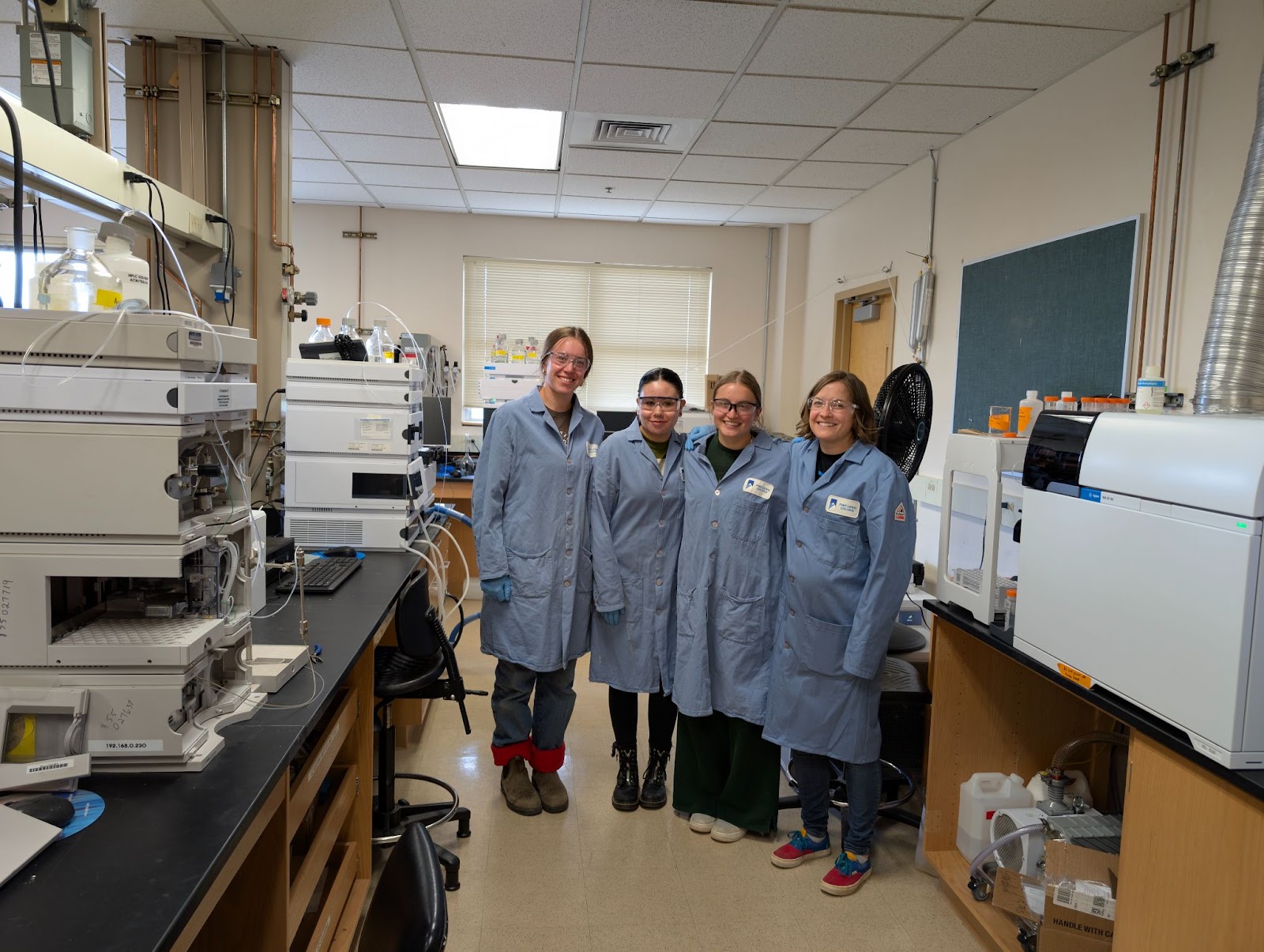

The team of student researchers, Liena Goddard, Morgan Montaño, and Oona Nelson, are excited to tackle this issue and bring awareness to women’s health.

“It’s so relevant to my life, literally every day and it’s really cool doing research that’s relevant to you,” Goddard said.

The research team stands next to their equipment (from left to right: Oona Nelson, Morgan Moñtano, Liena Goddard, and Dr. Callie Cole).

Last semester, the team analyzed four brands of tampons purchased in Durango and found lead exceeding the EPA drinking water limit (15 parts per billion) across all brands. They also quantified arsenic in half of the brands.

This semester, the researchers seek to determine whether these compounds leach out of tampons which could pose public health concerns.

“We are measuring how well or how efficiently lead, cadmium and arsenic leach out of tampon material into a menstrual fluid simulant,” said Cole.

Following the recipes of existing publications, the team created a menstrual fluid simulant, which “replicates all of the natural things that occur in blood and vaginal fluid,” said Nelson.

The simulant consists of proteins, glucose, phosphate buffer and lactic acid used to adjust the pH of the solution, Nelson explained.

Tampons were exposed to the simulant for either four- or eight-hour incubation periods. The simulant was then analyzed using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer to determine if metals had leached out of the tampons.

Tampons soak in menstrual fluid simulant.

Like most mass spectrometers, the ICP-MS quantifies elements in a sample by separating ions based on their mass to charge ratios.

What’s unique about this instrument, said Cole, is the plasma generated to ionize atoms. It runs between 1000-6000 Kelvin, roughly the temperature of the sun’s surface, Cole explained.

Plasma generated inside the ICP-MS instrument

ICP-MS instruments are typically used in analytical chemistry experiments and few biological substances have been run through them before, said the team. This has posed many challenges.

“No one has ever run menstrual fluid simulant on an ICP-MS before,” Moñtano said.

So, the researchers trail-blazed and tried it.

“It actually reacted with the nitric acid in the machine and it caused gooey clumps to form in our sample which does not do well with the machine,” said Moñtano.

A round of cleaning led back to square one.

The team realized sample preparation was required.

“We had to figure out how to basically clarify the menstrual fluid simulant and get the proteins out of it before we could run it on the ICP-MS,” said Moñtano.

They first tried clarifying the viscous solution by pushing it through a 0.45-micron filter.

“There was just no way,” said Nelson.

They then scoured existing research papers and ended up replicating the procedure of one which detailed how to clarify blood for ICP-MS analysis.

“We attempted to do their sample prep and it didn’t work well,” said Moñtano. “We had some challenges with instrumentation – some challenges getting instruments to the right temperature to be able to heat it as those papers did.”

The attempt ultimately failed leading to a messy cleanup and back to the drawing board, Moñtano said.

After further research, the team finally found a viable preparation method thanks to a new article published just days before their lab session in February 2025, Nelson said.

It explains how to clarify human albumin to run on an ICP-MS which was helpful since the main protein containing ingredient in the menstrual fluid simulant is bovine albumin, said Moñtano. Given that these proteins were similar enough, the clarification was successful.

In March 2025, the researchers obtained preliminary results.

“We were unsuccessful in seeing metals migrate out of the tampon,” said Cole. “So that’s actually really, really good – totally sweet negative result which is good for public health!”

The team will present this semester’s findings at the Spring 2025 Research Symposium on April 24.

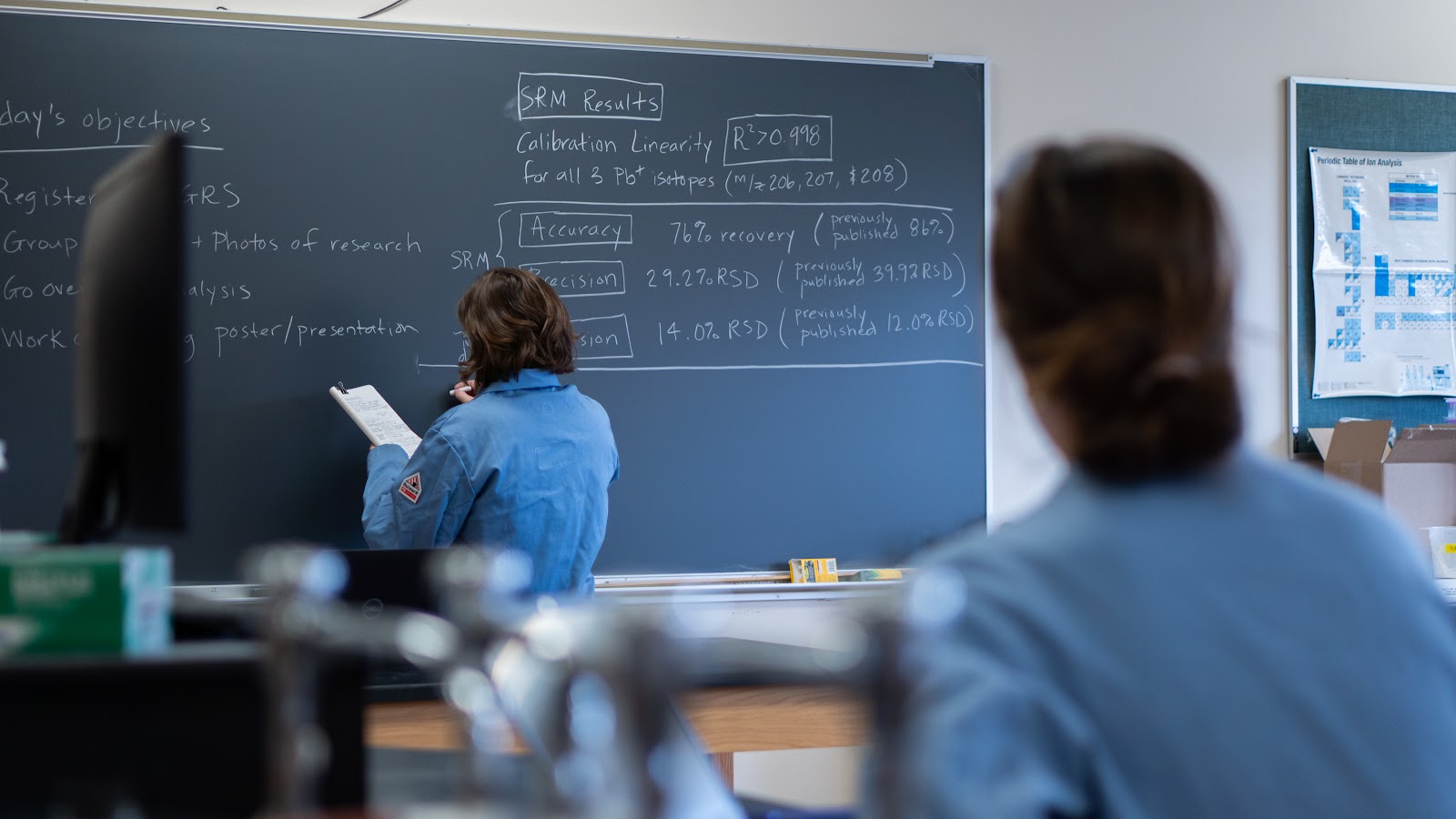

Researchers discuss data.

Thus far, the researchers have been funded by internal FLC grants: The Pay It Forward grant through the Undergraduate Research Department and First-Year Research Experience program through the Chemistry Department.

“Internal grants at Fort Lewis College are just fantastic for these preliminary projects where they’re curiosity based because a lot of the times you need that preliminary data to get a larger grant to fund a longer project that leads to publication,” said Cole

In fact, the researchers hope to publish their findings in the future and continue investigating women’s health.

“We’ve got some preliminary work,” Cole said. “I absolutely hope to follow up and publish this.